It wasn’t that long ago that we had a future.

Don’t worry, we still have one now. The sun isn’t going to blow up, a disease isn’t going to wipe us out… but that isn’t what I’m talking about. In a weird kind of way the future in our collective cultural mindset used to be a place, not just a time. And it was a place which had clear, definable differences from the present. We might not have known exactly what it was going to be like, but we knew it would be different and we knew that there was a path we could follow to get there. We even had phrases for it: ever hear someone talk about “building a bridge to the future”? Nowadays, that seems as quaint as talking about having a footpath to 5pm.

When I’m watching or reading or playing something set in the future, I want that setting to have the same sense of possibility that it did before. And I want it to be used.

Let me explain a bit. The things that are most important to me in a story are people, believe it or not. Plot and storyline are also important, of course, but what I really want are well-realised characters. I’m interested in characters who can cry, laugh, hope, make mistakes, and try again… characters who are a lot like real people, in other words. Apart from anything else it makes it easier to identify with them and their motivations, and I don’t think I’m alone in realising this. Flaws and plausibility are closely connected, in other words.

So what does this have to do with the future? Well, stories – even sci-fi stories – are about characters, not technology. People want to read about a brave-but-morally-conflicted pilot, not a Mk.19 Autonomous Warhead Delivery Subsystem (although as I write this, I realise that there is sure to be an anime along these lines. Doubtless one in which the AWDS has the shape of a well-developed woman for no readily explainable reason, and a variety of improper yet thrilling relationship issues with other characters.)

Where was I? Oh yes, stories are about characters. And the best-realised characters are flawed. Things get damaged if you use them. People make mistakes, get lazy, forget to clean up… and all of that has an effect on the environment they’re in. In other words, the future they live in looks distinctly second-hand.

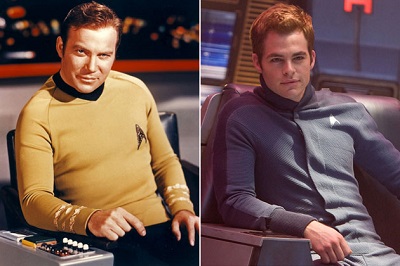

This isn’t an opinion that is universally shared, mind you. Once upon a time everyone thought that the future would be clean! Sleek! Efficient! Occupied by square-jawed white men in snug uniforms, who stared steely-eyed at the camera! And there’s still a strong body of opinion to the effect that if you want to portray the far future, that’s what you need to do. I don’t want to be too critical of this, because it’s a stylistic choice as much as anything. But I think it misses the point that I was making above. Anywhere which has people living in it – actual real ones, not the stereotypes it’s so easy to stop with – will not look like a well-kept model. Neither will the people who live there.

As I said, I’m not the only one who’s realised this. The term “used future” dates back to 1977, when George Lucas told his set designer that he wanted the Millenium Falcon to look like a ship from 2001: A Space Odyssey that had aged 200 years. It looked like it had been in service for a long time – that it had its own stories, and was more than just a way of doing the Kessel Run in 12 parsecs. All of this provided a location which told audiences volumes about the setting – and the characters within it. In a way, the ship was verging on becoming a character itself.

And in 1979, Alien set the benchmark for this. The starship Nostromo took the hard-used and worn aesthetic from Star Wars and then applied a thorough coating of industrial grime. This applies to the crew as well. They’re not astronauts or heroes, they’re basically truck drivers in space, and thus totally unprepared for what they end up having to deal with. This makes it a lot easier for us to identify with them and engage with the story.

If you’ve read some of the things I’ve written elsewhere, you’ll know why this is such a big deal for me. Sure, characterisation is number one, followed closely by plot and story. But what helps me suspend my disbelief and get immersed in a story is the level to which it’s internally self-consistent. And sometimes, it’s the smallest things which can help with this. Seeing the dents and scrapes left by people who have bigger worries than keeping things pristine supports the illusion that this is a real place, inhabited by real people. I want to see things that show they have a life outside what the plot mandates. Maybe their armour is commendably hacked and battered, proving that it’s been doing its job. Or the reactor that supplies power to the ship got replaced with a smaller one some time ago, so you can’t run everything at once. Cabin 3 is always a little colder than the rest of the ship. Someone leaves their toy dinosaurs on the pilots console… you get the idea.

And there’s only one way I want things to be shiny.

Question of the post: What do you want your fictional future to look like? And what helps you get immersed in a setting?

I really like the way you write, young Mr Watson.

Really. Like. It.

(Or as they said elsewhere in a galaxy far far ago, “The talent is strong in this one.”

I’m off to read some more.

Christmas in Japan? Tanoshi mitai!

LikeLike

Thank you! I’m very pleased to hear your good opinion. Although I know there is still much to be done, I hope that things will improve. This blog is, I hope, a step towards that.

LikeLike

To me it was always the bridge between the two that holds an appeal. The characters (as you rightly point out) are vitally important. They’re the mechanism for moving the story forward, the vehicle. The setting is also important. But I feel the link between is very telling of a story, the various levels of wear and the way society works with, or around, that. I might call it “acceptance” for want of a better term.

Times of plenty may lead to well-crafted structures, orderliness etc. because money is no object and showing off is often what happens. Higher technological levels is oft demonstrated by cleanliness, if the tech is pushed far enough you can end up with the equivalent of modern elves. Hardship and poverty can lead to a make-do attitude of the characters. All of this I find most interesting when characters from disparate levels of acceptance meet. The conflicts between the two leading to the meat in the story, and often to comical elements (see Demolition Man and the 3 seashells, a wholly unnecessary plot device but enough to demonstrate that the displacement can be jarring without needing to show every last stumbling block for the poor character).

Without the characters having levels of acceptance, little nuances of behaviour, they may as well be on a stage. Their response to their setting alone says a lot. Acceptance, desire, jealousy, disgust.

So, how do I want my future? I want my future varied. I want everything from pristine streets with brand-new robot cleaners through to decrepit 1950’s style tower-blocks and people making do. I want the Millenium Falcon _and_ the Imperial Lambda-class shuttle. I want people to always have something to aim for because stagnancy sucks.

LikeLike

That’s a very good point. If there’s one theme that’s common to all speculative fiction, it is “divergence”. Seeing different ways of being is key to experiencing it, and that’s one of the reason I like roleplaying games so much – I get to explore and react to what I encounter, albeit in a limited fashion. So yes, I agree that variety is important too. And as you say, when people from one society encounter a different setting things usually get very interesting.

It’s also interesting what our reactions say about ourselves… but that’s a mirror I’m not mentally prepared to hold up just yet!

LikeLike

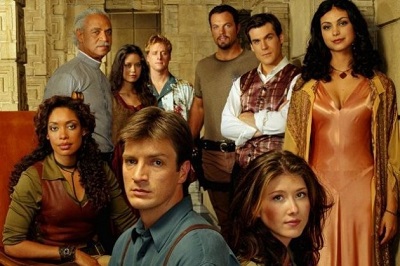

I love me a rustbucket future. The Firefly example is especially good for this point, I feel, because it’s not ENTIRELY a rustbucket world, but the characteristics of the ships and the colonies add characterisation in setting–when compared to the clean, streamlined Apple Store aesthetic of the Imperial ships and settlements, it shows a clear divide between the two sets of characters and works very nicely as a visual cue to the tension between the classes.

Pacific Rim also has a lot of fun with this–not only is the machinery all a bit worse for wear, but a lot of it has personal touches that act as extra little details to build the characters. Worldbuilding in the details is everything!

LikeLike

That ties in to what Mike was saying about the contrast between futures. The same divided aesthetic is in Star Wars too – again, the contrast between the clean and sparse Imperial designs and the older and more used Rebel Alliance drives home some of the differences between what they represent.

And yes, attention to detail in worldbuilding is very important. It can be the difference between ‘good’ and ‘great’, and I really appreciate it when it gets done well. But it can’t rescue something that is flawed at a more fundamental level, so I suppose I think of it as a very important extra feature.

LikeLike

Pingback: Liebster Award Nomination | Speculative OP